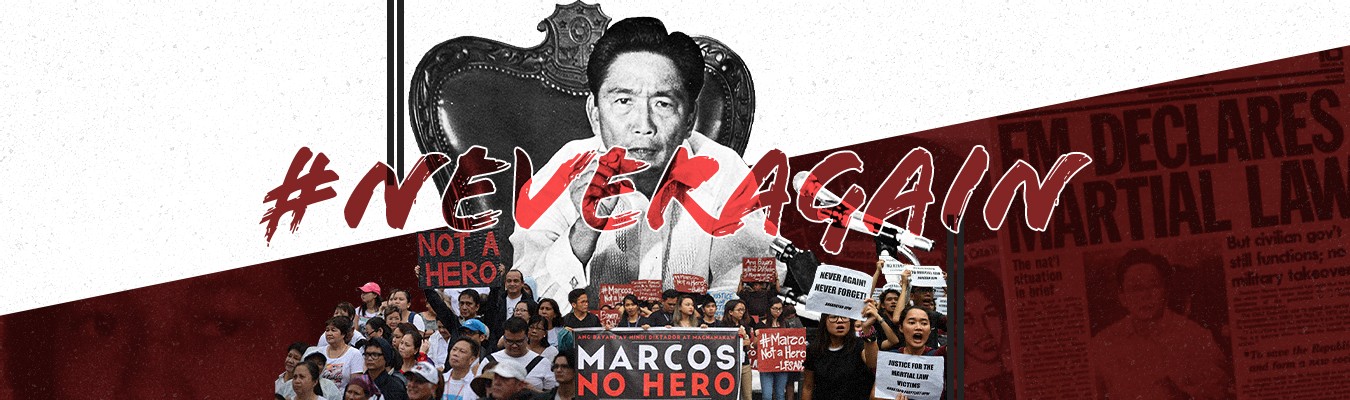

On September 21, 2021, during its 49th anniversary, Filipinos look back at one of the darkest chapters in the Philippine History, the Martial Law —a state of lawlessness that had enthralled the country and placed the Filipino people, and democracy in jeopardy,

At 7:15 in the evening of September 23, 1972, the late President Ferdinand Marcos appeared on the national television, and radio to formally proclaim that the Philippines was under Martial Law.

Why Marcos declared Martial Law

Specifically, when Marcos signed Proclamation 1081 on September 21, 1972, he cited the “communist threat” as justification. His diary, meanwhile, said the proclamation of Martial Law became a "necessity", following the supposed ambush of then defense secretary Juan Ponce Enrile. The late president also cited that the Communist force (that obtained weapons from China) planned to overthrow the government and to wreak havoc to the peaceful lives of ordinary Filipinos.

In response, Marcos declared that he would place the Philippines under a state of Martial Law, as according to the president’s powers described in the 1935 Philippine Constitution. Such powers included command over the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to maintain law and order, as well as exclusive decision-making powers for whether or not a person would remain detained for any crime.

Albeit there were reports which claimed that the said supposed ambush of Enrile was staged as claimed by Oscar Lopez and his family who lived near the area where it happened. Enrile, in his 2014 memoir and documentary, insisted that it was all real.

However, prior to Enrile’s 2014 documentary, the Official Gazette says that in February1986, Enrile seemed to switch sides, amid the historic People Power Revolution in EDSA, wherein he admitted to the public that the ambush incident was just staged to justify the implementation of Martial Law.

Although the declaration was made on September 23, the actual document had been signed September 21, 1972 due to a special superstition Marcos had about numbers.

The dreadful events during the Martial Law

On September 22, 1972, 49 persons from the Greater Manila Area were immediately arrested, by the military, among them three senators, three congressmen, two provincial governors, four delegates to the Constitutional Convention and eight newsmen. First on the list was opposition senator and main political rival Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr.

According to the Official Gazette, Marcos ordered a “viva voce plebiscite” on January 10–15, 1973, whereas the voting age was reduced to 15 to ratify the new Constitution. Military men were placed prominently to intimidate voters. Reports indicated that mayors and governors were given quotas for “yes” votes on the constitution and negative votes were often not recorded. Results report that 90 percent of the citizens have voted for the constitution even though some communities did not participate in the “citizens assemblies.” Over the next few years, Marcos held four more plebiscites—in 1973, 1975, 1976, and 1978—through citizen assemblies to legitimize the continuation of martial rule.

He also “intimidated” the Supreme Court according to the article, to approve it. Using the carrot-and-stick method on the justices of the Supreme Court, President Marcos was able to force the Supreme Court to uphold martial law and the new constitution. Previously, around 8,000 individuals, including senators, civil libertarians, journalists, students, and labor leaders, were arrested and detained without due process upon the declaration of martial law

With many of them filing petitions to the Supreme Court for habeas corpus; a fundamental right in the Constitution that protects against unlawful and indefinite imprisonment, they challenged the constitutionality of the proclamation. However, the Supreme Court issued its final decision, in Javellana v. Executive Secretary, which essentially validated the constitution

According to the president's General Order No. 4, it is illegal to be outside your home between 12mn and 4am. According to the order, people outside their homes from 12mn to 4am will be summarily arrested and held in the nearest military camp overnight. If the military finds "valid and compelling reasons" for further detention, violators will be transferred to the nearest prison camp; otherwise, they will be released the next day. Exemptions were made for those with a written authorization from the military commander in charge of one's area of residence. This announcement was made on September 22, 1972, a day after President Ferdinand Marcos signed Proclamation No. 1081, declaring the implementation of martial law throughout the country.

During Martial Law, there were 107,240 primary victims of human rights violations, prompting to fast growth of opposing groups. According to Official Gazette, party growth was fastest in areas where human rights violations were high due to military presence. By the late 1970s, the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) could claim a guerrilla force of 15,000, around the same number of squads, and a “mass base” of around one million. While AFP forces also experienced rapid growth during this period and were better equipped, there was a difference between the two.

According to Gregg Jones in his book Red Revolution: Inside the Philippine Guerrilla Movement that “[d]espite a high rate of illiteracy, communist soldiers could explain why they were fighting and what they were fighting for. In contrast, most government soldiers were poor peasants or slum dwellers who enlisted in the government army not out of political conviction but because of economic deprivation.”

Also,there were an approximately 70,000 people arrested, mostly arbitrarily without warrants of arrests, 34,000 people were tortured, 3,240 killed by the military and the police, and 464 media outlets were closed — 8 major English newspapers, 18 vernacular, Spanish and English language dailies, 60 community newspapers, 66 TV channels, 20 radio stations, 292 provincial radio stations after declaration of martial law.

Sources: Philippine Daily Inquirer, Rappler, Martial Law Museum, and Official Gazette